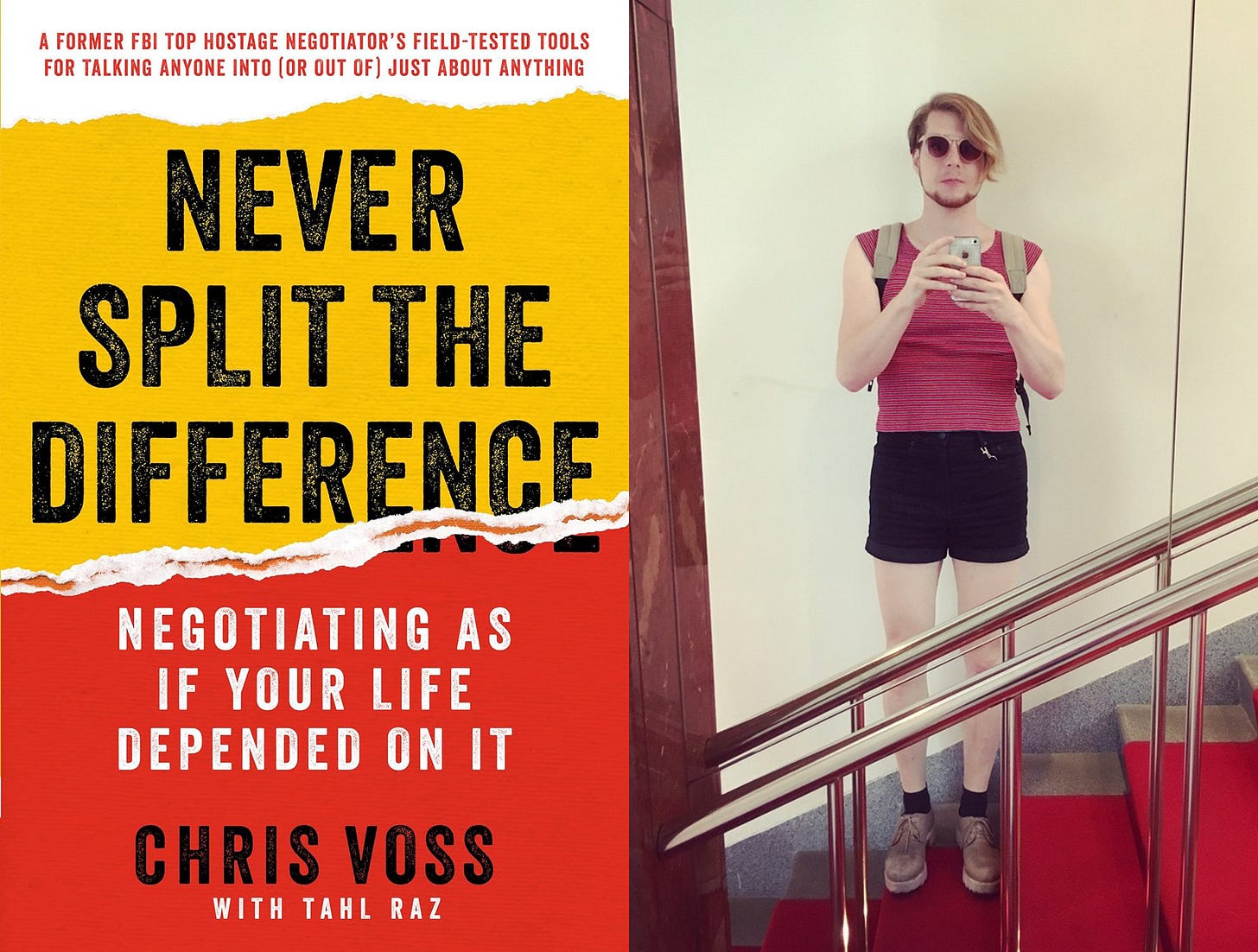

In July 2017, I was on the train to Prague for a little vacation. Across the aisle, I saw a suit-wearing person holding a flashy looking book, brightly yellow and red, with an even more flashy title: Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On It, written by Chris Voss, former FBI hostage negotiator.

Oh my. So cold-hearted, violent, inhumane. What a horrible book that must be, I thought, and quickly looked away to hide the confused-judgy expression that was surely written all over my face. I was appalled, but at the same time, in some kind of obscene way, I couldn’t deny that my interest was piqued.

Since I hadn’t prepared anything else to read on the train, I downloaded a sample, just for the fun of confirming that my suspicion was right, that the book was really as awful as it seemed.

And, well, what can I say: I was wrong. I ended up reading the whole book.

To my surprise, the main insight I took from it was how centrally important true, deep empathy and trust is for working things out with other human beings. Especially in a work context, I now see the basis of good negotiation skills as emotional intelligence combined with an unshakeable collaborative spirit (not to be confused with people-pleasing).

Even though Chris Voss doesn’t apply his advice to leadership per se, hearing his analyses of real-life cases helped me reflect on my own way of working with people. It helped me sharpen my understanding of the mechanisms that underly all kinds of human interactions, including team meetings, 1-on-1s with engineers, and conversations with other leaders and stakeholders across the organization.

So, how do these insights translate into practical leadership skills? Let's explore three key negotiation principles that I’ve found invaluable in my technical leadership role:

Negotiation is the heart of collaboration

Make allies, not enemies

Yes is nothing without how

I will begin each section with quotes from the book and then explain how applying it can make you a better leader.

Ready? Alright, here we go.

Negotiation is the heart of collaboration

“Negotiation is the heart of collaboration. It is what makes conflict potentially meaningful and productive for all parties.”

“A good negotiator prepares, going in, to be ready for possible surprises; a great negotiator aims to use her skills to reveal the surprises she is certain to find.”

At the time I was reading this advice, around 7 years ago, I was leading the development of multi-clip editing in Ableton Live. It was a project that required a great deal of restraint to avoid getting lost in the details. In other words, a big part of my job was to say no to a lot of people, both inside and outside of my team.

As the project got closer to the finishing line, I was still hoping that we might be able to ship an extended version. We had a prototype implementation, we had validation from successful user tests. Now all we needed to do is produce maintainable, tested code. That’s when I got to hear a no from the product leader one level up. Sigh.

Saying no can be just as disappointing as hearing a no. It is basically the opposite of one of the most enjoyable things about leading a team of brilliant software engineers: feeling their excitement about the possibilities.

When a no is needed, how can you avoid deflating the energy as much as possible? This is where good negotiation skills come in. In short, you want to:

Build on shared values. Be clear and open about your desire to deliver the best possible product. Pay close attention to the emotional energy in the room, which is sometimes reflected in people’s postures. It should feel like all of you are looking in the same direction, solving a problem together, not looking at each other as opponents. Consider creating a visual representation together to center the conversation around.

Avoid an antagonistic framing. If you keep feeling like you need to convince “them”, you’re probably not ready yet to have the conversation. Nobody needs to be convinced if they can discover the reality of the constraints themselves.

Uncover barriers to remove. Get together and give everyone the opportunity to share their doubts and concerns, anything that might stand in the way of a successful delivery. Then ask, “How could we get it done despite these obstacles? Is there anything we’ve overlooked?” Remain open to surprises until the end. With the combined intelligence of your team, a no might turn into a yes.

You know it’s working if a clear conclusion emerges like a shared discovery.

In one case, I suggested two opposite prompts to my team:

Why we should go for it

Why we should not go for it

We went through each of the three feature variants we had been considering and first made a case for it and then a case against it. This was at a stage where we already understood the options quite deeply. We had created design mockups and partially working protoypes. Everyone was eager to get started on implementing it “for real.”

However, after allowing ourselves to be critical about something we were excited about, it became evident that none of the options was worth the effort and the complexity it would add to the software.

Disappointing? Yes. But because we had discovered the answer for ourselves, it still felt like a successful exploration. We quickly reoriented ourselves and got working on something that was actually achievable and worth doing, not something that was bound to be a complicated compromise.

Make allies, not enemies

“We wanted them to see things our way, and they wanted us to see it their way. If you let this dynamic loose in the real world, negotiation breaks down and tensions flare.”

“Calibrated ‘How’ questions […] put the pressure on your counterpart to come up with answers, and to contemplate your problems when making their demands.”

“Never create an enemy.”

You’re probably familiar with the strange feeling when you’re observing two people talking past each other. You can see what’s happening and it seems that it could be so easy for them to come together and find common ground, but somehow they can’t.

Sometimes we are those people. And typically, the hidden cause in such situations is fear. Here is how it works:

Let’s say you’ve worked hard to arrive at a position that a stakeholder disagrees with. You haven’t even had a conversation about it, but somehow you can sense it and it makes you feel threatened. “Why don’t they trust me to do my work? Why are they overstepping their territory and making it harder for me to defend my position in front of my team?”

See how the whole framing of the situation is adversarial? And just like that, we’ve created an immensely powerful enemy in the virtual world constructed from our beliefs. They are out there waiting to crush you. And you are here at your desk, nervous, just trying to do your job, alone and without support.

How can you prepare yourself for negotiating with them?

The key, as hard as it may seem, is to let go of fear. If it feels like everyone involved is working hard to defend their territory, that’s a dysfunction and a mistake.

“Never create an enemy” says Chris Voss, and I agree: more often than not, enemies are created, not just encountered out of nowhere. What’s needed to avoid creating enemies is a radical reframing of the situation.

If a stakeholder has strong opinions about a piece of work you are responsible for, that means that they care about the outcome. And if they care about the outcome, that means they can be a valuable source of energy and of intelligence. All you need to do is get over yourself and open your ears to their perspective.

As you allow yourself to go there, your mind may involuntarily generate fearful thoughts again. “What if I can’t defend our plan? Will they make me feel like a failure? What if there are other stakeholders out there who have yet another position? Will my team get crushed up in the middle of a fight between giants?”

Observe the thoughts. Recognize them for what they are. It’s just the voice of fear. It’s a sign that you want to do a good job, you want to be on the right path, make good decisions that lead to the desired outcomes, and you want to be supported and appreciated by the people around you. Those are fair wishes. It’s just that being tense and defensive won’t get you there.

Having been on both sides of such situations, I can tell you this: it can be incredibly hard for an influential person to navigate the power differential and contribute to a project that’s led by an anxious person. Ultimately, the project lead has more immediate influence on what will be built than anyone outside of the team. So it is possible that there is fear on both sides: fear of building the wrong thing, fear of missing the opportunity to give it your best shot.

How can the two sides come together?

I’ve learned to defuse such situations with a simple recipe:

Acknowledge and be thankful for the other person’s care. It’s not easy to share a critical position! It takes courage.

Invite and welcome their perspective. Make these connections a priority.

Listen, listen, listen, and make sure you understand what motivates them and what experience their position is based on. “See things [their] way.”

If something they say doesn’t make sense to you, don’t gloss over it. Don’t try to appear smart. Clearly it makes sense to them, so if you can’t see it yet, there might be a miscommunication.

Ask open-ended How questions to activate them into coming up with solutions for you. E.g. “How do you imagine X in more detail” or “how do we solve problem Y.“

Try it. You might be surprised how quickly the most critical stakeholders will take on your most difficult problems and collaborate with you on solving them. Experienced and influential people can become a valuable resource who help you aim high and move forward while keeping things simple.

About a year into my conscious negotiation journey, I had become very comfortable dealing with all sorts of opinions and perspectives. I was so eager to hear everyone's thoughts that I organized a series of events to which I invited the whole company. Typically we were between 20 and 30 people. Each time, I’d present a small selection of unfinished, experimental ideas and we’d start discussing them and collecting notes.

The strong impression that stayed with those who attended was that if they had ever anything to say about my work, I’d probably be happy to hear it. And they’d be right.

Yes is nothing without how.

“Don’t look to verify what you expect. If you do, that’s what you’ll find. Instead you must open yourself up to the factual reality of what’s in front of you.”

“[Negotiation is] a process of discovery. The goal is to uncover as much information as possible.”

“Yes is nothing without how.”

Projects are often divided into two stages:

Discovery — Understand, define, and refine the problem. Ideate and test hypotheses with prototypes. Investigate desirability and feasibility.

Delivery — Iteratively develop the solution.

Between these stages, there is a crucial checkpoint: the Go/No-Go decision, or in simple negotiation terms: yes or no.

If you’re an optimistic person with a “can do” attitude like me, you might wonder: what’s the point of all that? Why not go straight to delivery? Shouldn’t the delivery process be iterative anyway, optimized for continually reducing risk and uncertainty?

There is some truth to that point of view and for small projects on the order of only a few months, I can imagine it working well enough. For anything bigger, it is advisable to take into account the impact the size and complexity of a commitment has on momentum and motivation over time.

What is more motivating:

A small yes to delivering a minor increment every two weeks?

Or a big yes to doing what it takes to solve a hard problem that’s worth solving?

Well, if you ask me, a big yes would be more motivating. It provides the big picture context, the vision that gives all the smaller commitments meaning and that guides decision-making along the way.

With purely iterative development, it can become blurry what the big problem really is that you’re trying to solve. There is no guarantee that the work will add up to something coherent and meaningful, even if each iteration produces “working software.” Just “working” isn’t good enough. What matters is that it solves a big and important problem.

So when Chris Voss says, “yes is nothing without how”, what I hear is: the value of a yes depends on the quality and depth of the investigation that went into it. Without being confident that the goal is both desirable and feasible to reach, the initial excitement about doing something challenging can fizzle out in no time.

That’s what a successful discovery phase accomplishes. “The goal is to uncover as much information as possible”, as Chris says, so that a big, motivating yes can be spoken with confidence.

It’s like when you’re sledding at a local park, where you have to laboriously climb up the hill again after each round. In contrast, a big yes that’s built on the confidence of sufficient discovery can be a continuous source of momentum, like endlessly sledding down serpentines in the mountains.

Ultimately, the negotiation doesn’t end with a yes. It ends when a project has been delivered. From a certain analytical perspective, every single interaction along the way is either its own tiny negotiation or part of a bigger negotiation.

Stepping away from the coffee machine to make room for your coworker is a negotiation. So is deciding whether to respond to a message on Slack while you’re in a meeting.

The more aware we are of the needs and desires and the complex constraint landscapes that surround our choices, the more we can use our intelligence, our problem-solving abilities, to communicate effectively and help people experience the joy of working towards shared goals together.

What about you

I hope you enjoyed this little exploration into the overlap between leadership and negotiation, the “heart of collaboration.” Back on that train, I had no idea it would become such a central and recurring topic for me. They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but I would add: it’s fine to judge — as long as that doesn’t stop you from reading it with an open mind to see for yourself.

In the years since, several growing leaders have shared their struggles with me and I’ve been able to give them support and advice.

Now, what about your situation? Let’s take a moment to reflect.

How are decisions made at your company?

How do leaders at your company get buy-in from people who are affected?

Are teams trusted to take responsibility for executing their plans?

How effective are conversations between leaders who have no clear hierarchical relationship to each other?

How common is it for your teams to talk about the need to refine and streamline the development process?

How common is it for your leaders to suggest a reorganization?

Weaknesses in any of the areas mentioned above can be a symptom of causes that are neither exactly organizational, nor cultural either, nor interpersonal, which makes them tricky to diagnose and address.

The real cause might actually be a lack of awareness of the fundamental role of negotiation in any instance of human beings coming together to do great things.

Did this article make you think of a situation at work? Feel free to send me a message and tell me about it. I’m always happy to chat about these things, listen, and share my perspective.